Heian Period

Court Intrigue and Classic Tales: The Heian Period’s Aristocratic Rise and Samurai Dawn

Court Intrigue and Classic Tales: The Heian Period’s Aristocratic Rise and Samurai Dawn

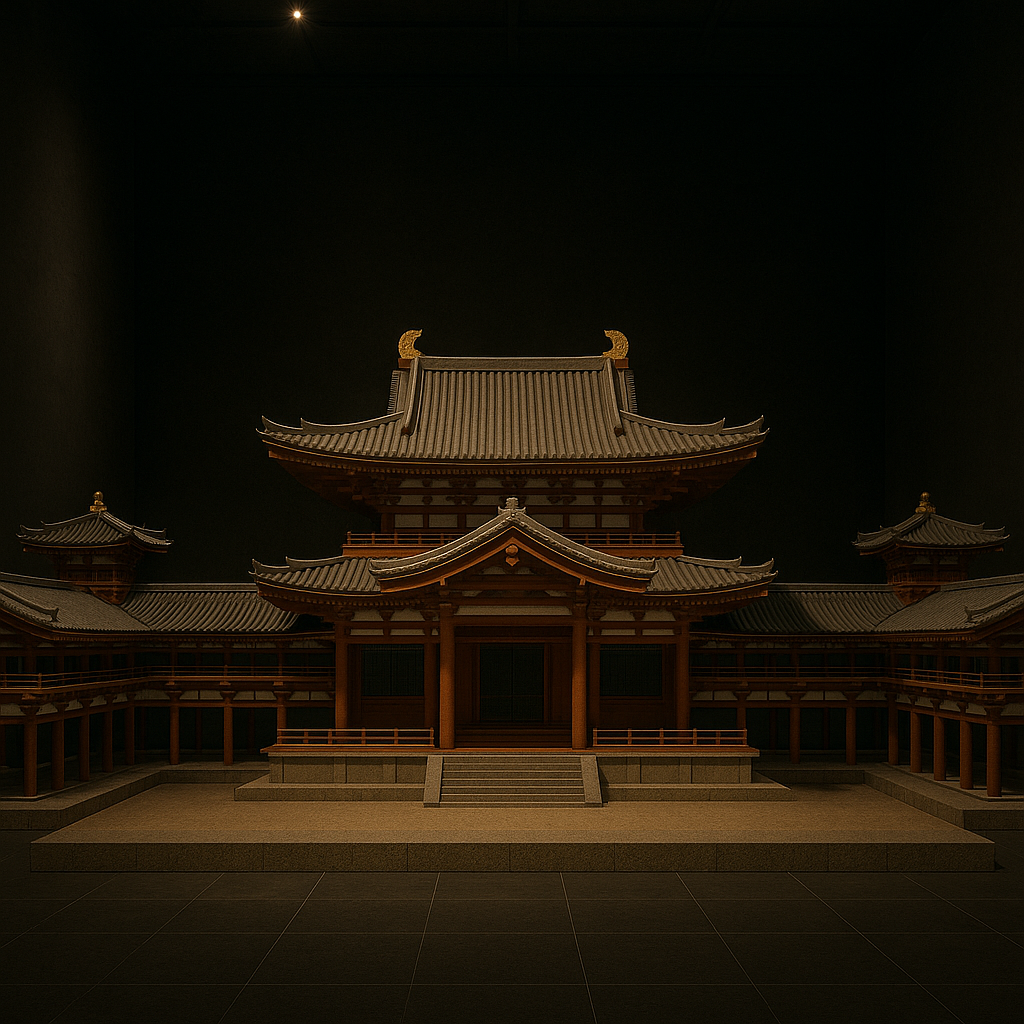

In our last installment, we watched Nara’s grand experiment unfold: temples sprouted like mushrooms, bureaucrats busied themselves with law codes and the populace endured a devastating smallpox epidemic. In the end, the court, weary of meddling monks and natural disasters, packed its bags once again. The Heian period (794–1185 CE) begins with a simple decision: move the capital. When Emperor Kammu relocated the court to Heian‑kyō (modern Kyoto) in 794 CE, he hoped to escape Nara’s problems and curb Buddhist influence. What he didn’t foresee was that his new city would become a byword for elegance, the birthplace of some of Japan’s greatest literature and the stage for the dramatic rise of the samurai. Throughout the Heian era, the ruling class would turn away from the heavy public works and rigid legalism of Nara and embrace a world of poetry, romance and opulent ceremony. Yet beneath this glittering veneer, cracks were forming: provincial warriors gained power, economic disparities widened and the Fujiwara clan’s grip on the court led to complacency. By the end of the period, the capital’s graceful palaces would burn as rival clans fought for supremacy, ushering in the Kamakura shogunate. To understand the Heian period, then, is to witness a society at its cultural zenith and political breaking point.

Literary brilliance was made possible by the development of kana, a syllabary derived from simplified Chinese characters. Early Heian scribes adapted Chinese scripts—specifically man’yōgana—to represent Japanese sounds. Over time, these characters were stylised into hiragana and katakana. Hiragana, with its flowing curves, became the preferred script for women’s writing and poetry; katakana, more angular, served as annotation in Chinese texts. The creation of kana liberated Japanese from Chinese grammatical constraints and allowed authors like Murasaki to craft prose that sounded like spoken Japanese. Court women, often barred from formal Chinese education, led the way in using kana, thereby shaping the language’s literary future [2].

The Heian period remains a paradox. It produced exquisite art, groundbreaking literature and architectural elegance. Aristocrats lived in a dreamworld of poetry and perfume, perfecting the art of feeling. The court refined Japanese into a written language of its own and nurtured religious syncretism that still characterises Japan today. Yet this beauty coexisted with neglect: tax evasion, environmental degradation and the suffering of commoners. The Fujiwara’s marriage politics led to stagnation, while their obsession with court etiquette blinded them to the rising power of provincial warriors. When the samurai came for Kyoto, they found a court unprepared for war. Our journey from Kofun tombs through Asuka reforms to Nara’s grand temples and Heian’s poetic salons highlights one thread: Japan’s constant adaptation. Each era borrowed from abroad, reinvented itself and then faced new challenges. In Heian, the adaptation took the form of writing systems and literature; in Kamakura, it would manifest as warrior ethics and administrative reforms. To truly appreciate the Heian period is to read The Tale of Genji, gaze upon a Heian scroll and sense both the twilight melancholy and the dawn of a new age.