Jōmon Period

The Cord-Marked Chronicles: A Humorous Journey into Japan's Jōmon Period (14,500 BCE-300 BCE)

The Cord-Marked Chronicles: A Humorous Journey into Japan's Jōmon Period (14,500 BCE-300 BCE)

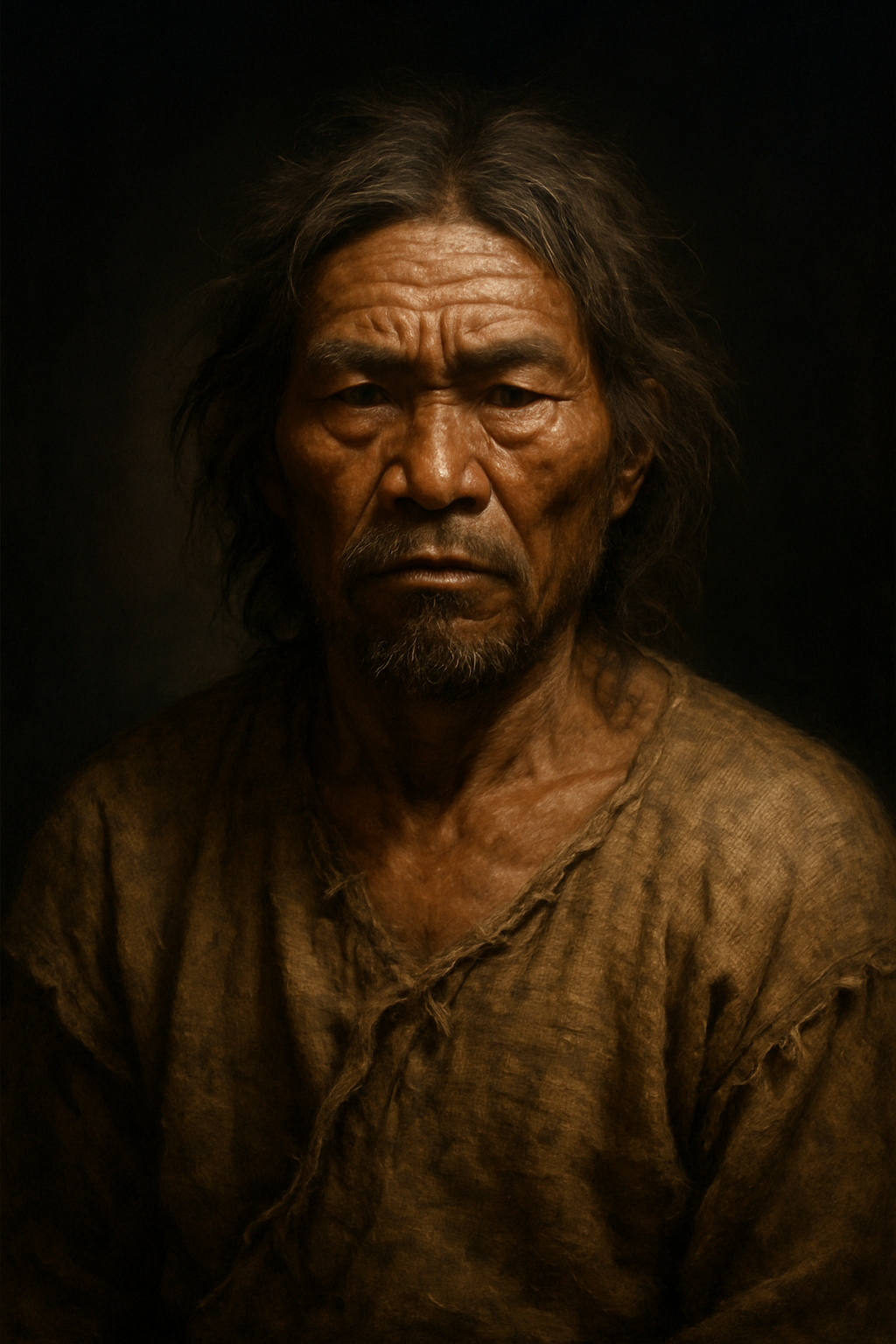

You may think history is all dusty scrolls and snooty academics, but the Jōmon period proves otherwise. Imagine a prehistoric Japan where folks lived in cozy pit‑dwellings, sculpted mind‑boggling flame‑rimmed pottery, dabbled in teeth removal as a rite of passage and produced some of the world’s earliest clay figurines. This article explores the fascinating Jōmon era (c. 14,500 BCE–300 BCE) with equal parts scholarship and sass. Prepare for cord‑marked pottery, dogū figurines, climate change drama and a finale featuring rice farming – because even prehistory knows how to throw a cliff‑hanger.

The term Jōmon means “cord‑marked”, referring to the rope‑like impressions pressed into their pottery [9]. Archaeologists see this era as Japan’s Neolithic period; it encompasses an enormous stretch of time from roughly 14,500 BCE to 300 BCE. These people were semi‑sedentary hunter‑gatherers who lived in pit dwellings arranged around central plazas, surviving on a diet of gathered plants, wild game and fish [1]. They lacked a written language, so their story must be pieced together from shell mounds and potsherds. Picture tens of thousands of years of family gossip, gossip we can only infer from discarded clam shells.

Life in Jōmon Japan was not as bleak as a caveman cartoon. The people built half‑buried houses with hearths in the floor for warmth and cooking [1]. These dwellings were grouped into villages near rivers and coasts, because why not enjoy a beach view? Initially, they were simple surface huts, but as we reach the Middle Jōmon, houses became more elaborate, with stone‑paved floors and separate walls and roofs [6]. Imagine upgrading from a tent to a charming stone‑floored bungalow. Thatch and other reeds served as roofing, while walls were packed with clay or bark. This architectural evolution hints that the Jōmon people had time for DIY improvements—perhaps the world’s first home‑makeover show. Food came from the land and sea. Shell mounds reveal that shellfish were a staple, joined by deer, boar, rabbit and duck [4]. Seasonal rhythms shaped their menu: hunting boar and deer in winter, gathering greens and fishing in spring, catching fish in calm summer seas and collecting nuts and berries in autumn [4]. Warm periods allowed them to venture into mountains or travel along the coast in search of resources [3]. Evidence from Kyūshū suggests that nut preparation – particularly chestnuts – was a central part of their diet [4].

The term Jōmon means “cord‑marked”, referring to the rope‑like impressions pressed into their pottery [9]. Archaeologists see this era as Japan’s Neolithic period; it encompasses an enormous stretch of time from roughly 14,500 BCE to 300 BCE. These people were semi‑sedentary hunter‑gatherers who lived in pit dwellings arranged around central plazas, surviving on a diet of gathered plants, wild game and fish [1]. They lacked a written language, so their story must be pieced together from shell mounds and potsherds. Picture tens of thousands of years of family gossip, gossip we can only infer from discarded clam shells.

Life in Jōmon Japan was not as bleak as a caveman cartoon. The people built half‑buried houses with hearths in the floor for warmth and cooking [1]. These dwellings were grouped into villages near rivers and coasts, because why not enjoy a beach view? Initially, they were simple surface huts, but as we reach the Middle Jōmon, houses became more elaborate, with stone‑paved floors and separate walls and roofs [6]. Imagine upgrading from a tent to a charming stone‑floored bungalow. Thatch and other reeds served as roofing, while walls were packed with clay or bark. This architectural evolution hints that the Jōmon people had time for DIY improvements—perhaps the world’s first home‑makeover show. Food came from the land and sea. Shell mounds reveal that shellfish were a staple, joined by deer, boar, rabbit and duck [4]. Seasonal rhythms shaped their menu: hunting boar and deer in winter, gathering greens and fishing in spring, catching fish in calm summer seas and collecting nuts and berries in autumn [4]. Warm periods allowed them to venture into mountains or travel along the coast in search of resources [3]. Evidence from Kyūshū suggests that nut preparation – particularly chestnuts – was a central part of their diet [4].

Because the Jōmon period spans more than ten millennia, scholars divide it into phases based on climate shifts and cultural developments [3]. Let’s take a whirlwind tour:

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Jōmon era is its ritual life. The increased production of female figurines and phallic images during the Middle and Late Jōmon suggests a belief system centered on fertility and nature [6]. These clay figures, known as dogū, come in various shapes—from heart‑shaped faces to goggle‑eyed “Venus” types. Many show exaggerated body parts and are decorated with patterns. Archaeologists propose that dogū were used for sympathetic magic: to absorb illnesses or misfortunes, then intentionally broken and discarded [6]. Several were found in trash heaps with missing limbs, indicating they were deliberately “sacrificed.” Another striking practice is tooth ablation. Around 80–90% of Late Jōmon skulls show teeth intentionally removed, likely as a rite of passage for adolescents or a symbol of marital status [7]. That’s right—the Jōmon people literally pulled teeth for cultural reasons long before modern braces. Talk about taking “no pain, no gain” to a new level! Burial practices also hint at belief systems. Bodies were sometimes interred in the very shell mounds that communities created by discarding seafood remains [3]. Stone circles may have served as communal ritual grounds [3]. These sites reveal a society deeply connected to both the earth and the sea, honouring ancestors and nature through ceremony.

Throughout the Jōmon period, climate change plays a starring role. Early on, the warming climate raised sea levels, separated Japan from Asia and forced people to adapt to island life [4]. During the Middle Jōmon, temperatures peaked, prompting migrations into mountainous areas and supporting larger populations [3]. However, the Late and Final phases saw cooling and resource decline, leading to population shrinkage and more regional variation [3]. This long‑term dance with climate demonstrates the Jōmon people’s resilience and ability to innovate – from adopting new fishing methods to experimenting with agriculture.

By around 300 BCE, communities in western Japan began cultivating domesticated rice, possibly in swamps or dry fields [3]. This agricultural innovation likely came with migrants from mainland Asia, who brought wet‑rice farming and metalworking. The combination of new technologies, different pottery styles and social structures marks the transition to the Yayoi period. Yet the Jōmon people did not disappear; they blended with the newcomers, leaving a genetic legacy that still lives on. Studies estimate that modern Yamato Japanese carry roughly 30% paternal, 15% maternal and 10% autosomal Jōmon DNA [8]. In other words, those ancient cord‑marked potters are literally in the blood of most Japanese people today.

The Jōmon era is more than just a prehistoric footnote; it is a foundational chapter in the story of Japan. These people developed some of the world’s oldest pottery, adapted to massive environmental changes and pioneered ritual practices that echo through centuries. Their artistic flair is evident in flame‑rimmed pottery and whimsical dogū figurines, while their resilience shines through their adaptation to climate swings and changing resources. The Jōmon story also reminds us that human history is rarely a neat linear progression; it is a tapestry of migrations, environmental pressures, innovation and cultural exchange. On a lighter note, the Jōmon period is proof that prehistoric people had style. They decorated their pots with cords, created jewelry, built comfortable houses and even engaged in body modification. If time travel were possible, an episode of “Jōmon Home Makeover” might be a hit: watch as a family upgrades from a pit hut to a stone‑floored lodge, complete with hanging dogū charms!

The Jōmon period may be shrouded in mystery, but it continues to captivate archaeologists, artists and history buffs. Its people left behind an abundance of pots, beads and figurines that tell stories of survival, creativity and belief. From Incipient hunters chasing megafauna to Late Jōmon artisans crafting magatama and dogū, their world was rich and dynamic. As we trace the threads from cord‑marked pottery to modern Japan, we see a continuity of cultural resilience. So next time you admire a piece of Japanese pottery or a whimsical figurine, remember the Jōmon – the original artisans of the archipelago.

Note: Footnote numbers correspond to the citations listed above. For readability, citations are included in brackets within the text.