Japan's History

Explore Japan’s past era by era with in‑depth posts and profiles of key figures.

Explore Japan’s past era by era with in‑depth posts and profiles of key figures.

14,500 BCE - 300 BCE.

Japan's earliest known culture was the hunter-gatherer Jōmon people. The name Jōmon means “cord-marked” and refers to the distinctive pottery patterns. They lived in pit dwellings and relied on fishing, hunting and foraging. Around 900 BCE rice farming was introduced, marking a gradual shift toward agriculture. Population expanded and by 3,000 BCE there were possibly hundreds of thousands of people.

300 BCE 250 CE.

The Yayoi period saw the introduction of wet-rice agriculture and metalworking. Stone tools were gradually replaced by bronze and iron implements, irrigation techniques were developed and communal granaries appeared. Populations grew and many settlements became large villages; the Asahi settlement covered about 200 acres.

250 CE - 538 CE.

Named after the kofun (large earthen burial mounds), this era marks the rise of the Yamato clan, who established control over central Japan and later formed the imperial lineage. Shinto beliefs emerged and elaborate haniwa clay figures were placed around tombs. New technologies—ironworking and improved irrigation—spread across the islands.

538 CE – 710 CE.

Increased interaction with Korea and China brought Buddhism and Chinese governmental models. Empress Suiko reigned with her nephew Prince Shōtoku as regent; Shotoku promoted Buddhism and issued a “Seventeen‑Article Constitution” to guide government. After Fujiwara no Kamatari launched a coup in 645, the Taika Reforms nationalised land and restructured administration along Chinese lines. The period ended following the Jinshin Incident (671–672), when Emperor Tenmu purged rivals to secure succession.

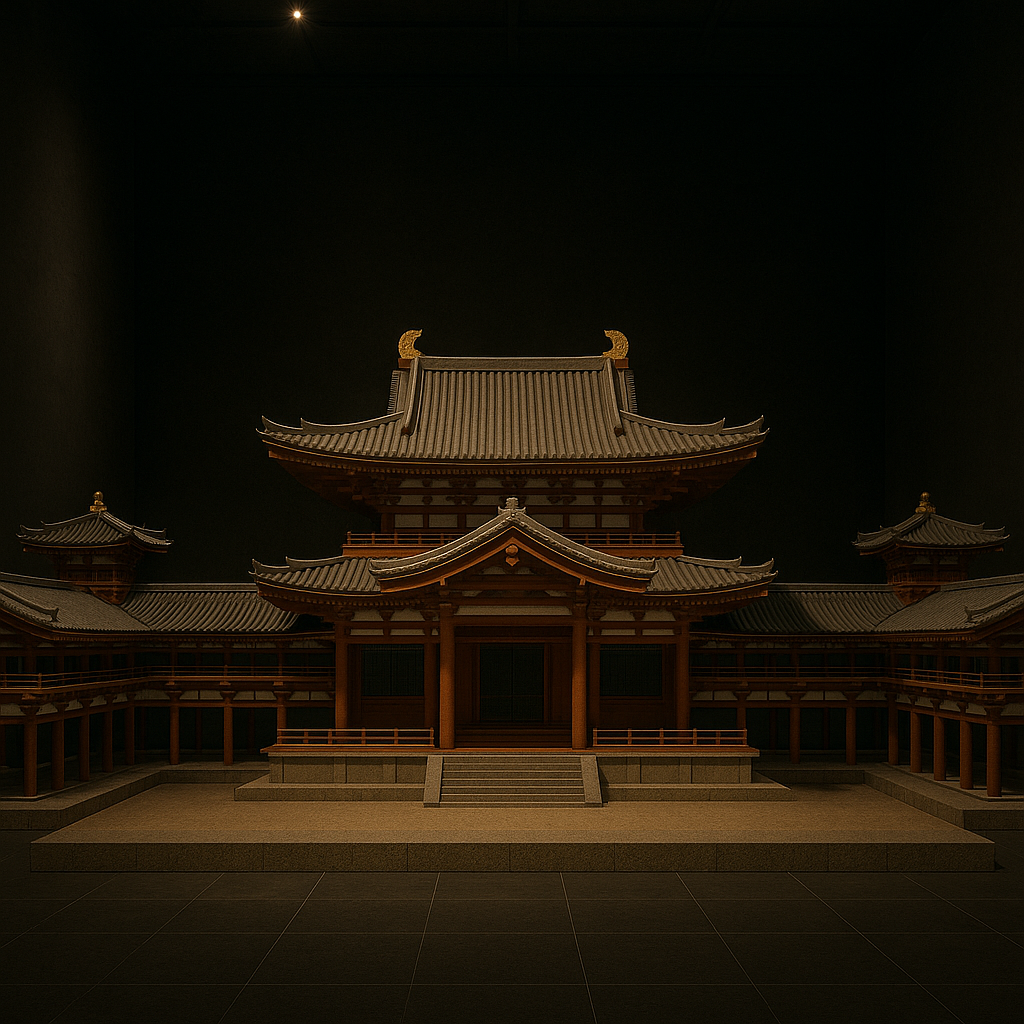

710 CE – 794 CE.

Empress Genmei moved the capital to Heijō‑kyō (Nara), Japan’s first permanent capital laid out in a Chinese‑style grid. The court attempted greater central control, but heavy taxation, forced labour and primitive tools led to peasant hardship. Smallpox epidemics (735–737) devastated the population, reducing it by 25–35 %. Emperor Shōmu promoted Buddhism; he ordered provincial temples and built Tōdai‑ji, housing a massive Great Buddha statue. Literary works including Kojiki (712), Nihon Shoki (720) and the Man’yōshū poetry collection (760) were compiled.

794 CE – 1185 CE.

The Heian Period is known for its art, especially poetry and literature. The capital was moved to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto), and the period is often considered the peak of Japanese culture. The samurai class began to emerge, and the Fujiwara clan dominated the politics of the time.

1185 CE – 1333 CE.

After victory in the Genpei War, Minamoto no Yoritomo established the Kamakura shogunate (1192), making Kamakura the seat of military government. Power gradually shifted to the Hōjō regents. The law code Jōei Shikimoku (1232) codified warrior ethics. Zen Buddhism (introduced by Eisai in 1191) and Nichiren Buddhism (founded by Nichiren in 1253) spread. The shogunate repelled Mongol invasion attempts in 1274 and 1281; typhoons (“kamikaze”) destroyed the Mongol fleets. Internal unrest and imperial restoration attempts led to the fall of the Kamakura government in 1333.

1336 CE – 1573 CE.

The Muromachi Period is characterized by the rise of the Ashikaga shogunate and the flourishing of culture, including Noh theater and ink painting. The Sengoku Era, or "Warring States" period, saw the country fragmented into numerous feudal domains, leading to constant military conflict. This era ended with the unification of Japan under Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu.