Heisei Period

From Boom to Bust to 21st‑Century Resilience: Navigating Japan’s Heisei Era (1989–2019)

From Boom to Bust to 21st‑Century Resilience: Navigating Japan’s Heisei Era (1989–2019)

Japan’s Heisei era, literally “achieving peace,” is one of those periods that looks serene on a calendar but feels like a roller‑coaster once you’re strapped in. After the long, turbulent Shōwa years, the country hoped Emperor Akihito’s accession on January 8 1989 would usher in stability. Instead, three decades of booms, busts, disasters and dazzling pop culture unfolded. This post continues our history journey, picking up the thread from the post‑war Shōwa era and following Japan through the end of the twentieth century and the opening decades of the twenty‑first. There will be bubbles (economic, not bath), nerve gas, giant robots, earthquakes, and a surprising amount of karaoke.

In the late 1980s Japan seemed unstoppable. The nation had rebounded spectacularly after the devastation of World War II, and by the Reagan–Thatcher years it was the second‑largest economy on earth. Tokyo’s property and stock prices went through the stratosphere. Skyscrapers sprang up across the capital, Japanese consumers enjoyed unprecedented affluence, and corporations flush with cash bought landmarks abroad—Rockefeller Center, Pebble Beach Golf Course, art works and even Hollywood studios. Conservative politicians and business leaders even wrote bestsellers predicting a Japanese century. Yet some worried that the prosperity was built on frothy speculation. It turned out they were right. What became known as the “Bubble Economy” relied on easy credit, real‑estate speculation and exuberant stock markets. Interest rates were kept low after the 1985 Plaza Accord, encouraging property developers and investors to borrow heavily. The Nikkei 225 index hit an all‑time high of 38,957 on the last trading day of 1989 before tumbling to 15,000 three years later. Land prices plummeted; some parcels in Tokyo’s Ginza district were suddenly worth a fraction of their purchase price. As the bubble burst, banks found themselves saddled with mountains of bad loans and consumers closed their wallets. The economic euphoria evaporated almost overnight, taking with it the sense of invincibility that had defined late‑Shōwa prosperity.

By the early 1990s Japan entered what became known as the “Lost Decade,” though it stretched on for more than ten years. Deflation set in, asset values withered and gross domestic product stagnated. Corporations refused to invest, banks hesitated to lend and consumers refused to spend. Standard economic remedies—stimulus spending and ultralow interest rates—failed to revive growth. The political establishment lost its aura of competence. In 1993 the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which had dominated politics since its formation in 1955, lost its majority and a fractious coalition briefly took power. Prime ministers came and went with dizzying frequency; over the three decades of the Heisei era there were seventeen of them. The revolving‑door governments struggled to tackle structural problems like an ageing population, rigid labour practices and a banking sector weighed down by bad debt. Yet the Lost Decade wasn’t all gloom. Japanese pop culture blossomed into a global phenomenon. Anime and manga franchises such as Pokémon, Digimon, Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball were exported worldwide, spawning conventions, costumes and global fan communities. The films of director Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli won international acclaim, with Spirited Away taking the 2003 Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. For every index chart trending downward there was a new cartoon character trending up.

Midway through the decade, Japan was rocked by two separate catastrophes that tested the nation’s resilience and shattered the myth of public safety. On January 17 1995, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake struck the city of Kobe and its surroundings. More than 6,400 people were killed and 41,500 were injured. Whole neighbourhoods collapsed or went up in flames, highways toppled and the Port of Kobe—then the world’s sixth busiest—was shut down for months. The disaster exposed weaknesses in building standards and disaster preparedness. Volunteers and non‑government organisations stepped in to fill gaps left by overwhelmed authorities, heralding a new era of citizen activism. Just two months later, on March 20 1995, the Aum Shinrikyō cult released sarin nerve gas on three Tokyo subway lines during the morning rush hour. Thirteen people were killed and at least 5,800 were injured, bringing terrorism and chemical weapons into the heart of the Japanese capital. The attack not only traumatised the nation but also raised uncomfortable questions about police surveillance of fringe groups and the resilience of densely packed urban infrastructure. The combination of the Hanshin–Awaji earthquake and the sarin attack spurred reforms in emergency response and spurred communities to organise their own preparedness networks.

Heisei politics were marked by volatility and soul‑searching. In the early 1990s, corruption scandals like the Recruit case eroded public trust in the LDP and led to the short‑lived Hosokawa coalition government. The LDP soon returned to power but in 2009 it was swept out again by the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), only for the DPJ to flounder amid factionalism and economic uncertainty. Conservative stalwart Jun’ichirō Koizumi became one of the few memorable prime ministers of the era, reigning from 2001 to 2006 and championing postal privatisation. Shinzō Abe, first elected in 2006 and returning in 2012, sought to revive the economy with “Abenomics” and reinterpret the pacifist constitution to allow more active self‑defense missions—a controversial step in a society still wary of militarism. Internationally, Japan tested the boundaries of its pacifist Article 9. During the 1991 Gulf War it sent money but no troops and was criticised as practising “chequebook diplomacy.” In 2003 a thousand members of the Self‑Defense Forces were dispatched to Iraq on a reconstruction mission—the largest post‑war deployment. The government also enacted legislation in 2015 allowing collective self‑defense, paving the way for Japan’s military to cooperate more closely with allies. These moves signalled a gradual reimagining of Japan’s security posture as the regional balance shifted and China’s power grew.

Even amid economic malaise and disaster, the Heisei era offered shining moments. In 1997 diplomats from around the globe gathered in Kyoto and adopted a landmark treaty to limit greenhouse gas emissions, the Kyoto Protocol, with 192 parties eventually ratifying the agreement. Japan’s own emissions reduction pledges were modest, but the protocol positioned the nation as a convener of environmental diplomacy. Sport provided another morale boost. In 2002 Japan and South Korea co‑hosted the FIFA World Cup, the first time the tournament had been held in Asia or jointly hosted by two countries. The spectacle brought millions of fans, billions of television viewers and a carnival atmosphere to cities from Sapporo to Yokohama. For a few weeks, talk of deflation and debt gave way to chants of “Nippon!” as the national team advanced to the knockout stage for the first time.

If the Lost Decade sapped economic confidence, it also fuelled a wave of creativity. Low growth and job insecurity pushed some young people to embrace alternative lifestyles and hobby cultures. The term otaku—once a pejorative for obsessive fans—was reclaimed as a badge of honour. Akihabara became a pilgrimage site for electronics, video games and idol merchandise. By the late 1990s Japanese pop culture was sweeping the globe, from Tamagotchi and Sony Walkmans to PlayStation consoles and Hello Kitty lunchboxes. Fashion subcultures like Shibuya’s kogal and Harajuku’s gothic lolitas took to the streets, while visual kei rock bands shocked and delighted audiences with elaborate costumes. The government eventually embraced this soft power under the banner of “Cool Japan,” using anime, cuisine and design to improve its global image and attract tourists.

As the new millennium arrived, Japan confronted structural headwinds that would define the later Heisei years. The population peaked at 128 million in 2010 and began to decline due to low birthrates. Rural depopulation accelerated, leaving shuttered schools and abandoned homes. Policymakers debated immigration, robotics and incentives for child‑rearing, but consensus proved elusive. The banking sector finally cleaned up many of its bad loans, yet deflationary pressures lingered. Efforts to reinvigorate the economy through monetary easing and fiscal stimulus met with only partial success, and the specter of long‑term stagnation (now dubbed the “Two Lost Decades”) remained. The early 2000s also saw new shocks. On October 23 2004 a powerful earthquake struck Niigata Prefecture, killing 52 people and injuring hundreds. Although far less deadly than the 1995 Kobe quake, it served as a reminder that Japan’s seismic vulnerabilities were ever‑present. The government invested in upgraded building codes, tsunami warning systems and community drills, and a burgeoning volunteer sector stood ready to respond.

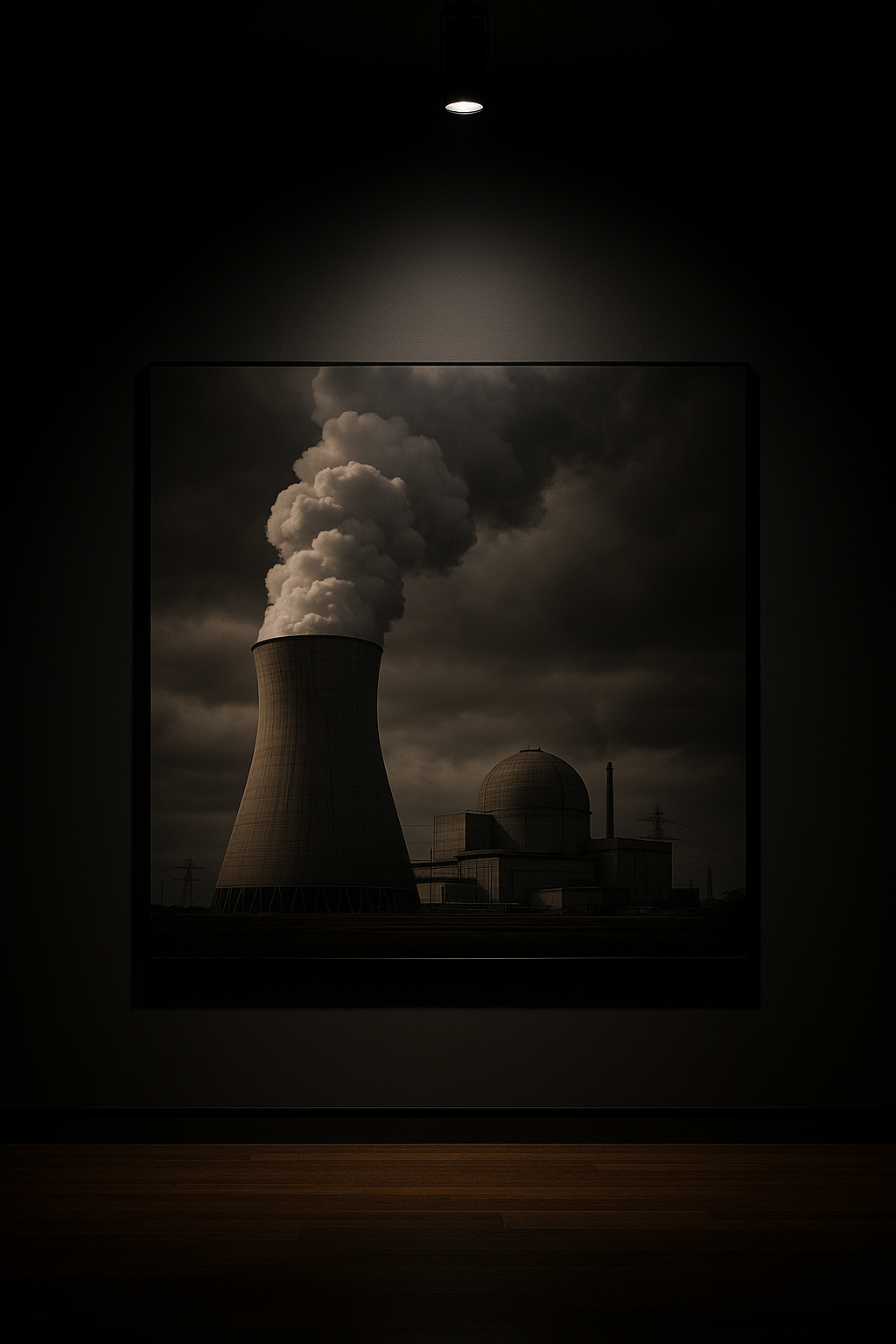

Nothing, however, prepared the country for the catastrophe of March 11 2011. At 2:46 PM a magnitude‑9.0 earthquake ruptured offshore in the Pacific, unleashing towering tsunami waves that engulfed towns along the Tōhoku coast. The tsunami overtopped seawalls, swept away buildings and vehicles, and surged inland for up to six miles. According to the Japanese government’s Reconstruction Agency, the disaster left 19,747 people confirmed dead and more than 2,500 still missing. It destroyed or damaged hundreds of thousands of buildings and generated debris that circled the globe. In the worst technological disaster since Chernobyl, tsunami waves knocked out cooling systems at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, causing reactor meltdowns and releasing radioactive materials. Though radiation release was largely contained, the accident raised global questions about nuclear safety. The government’s response was criticised for slow evacuation orders and confusing communication. Nevertheless, the courage of firefighters, plant workers and local residents in the face of unimaginable danger won admiration. International aid poured in, and Japan marshalled massive reconstruction funds to rebuild devastated towns. The tragedy also spurred debate over Japan’s energy mix: nuclear power was mothballed while renewable energy and conservation gained traction. Communities along the coast embarked on ambitious seawall projects and relocation plans, though demographic decline complicated redevelopment.

The disasters of 1995 and 2011 catalysed the growth of Japan’s civil society. Volunteer groups and non‑profit organisations mobilised to deliver supplies, rebuild homes and provide psychological support. Many of these groups continued working long after the headlines faded, filling gaps in social services and pressuring the government to improve preparedness. During the Heisei era, women’s participation in the workforce slowly increased and debates about gender roles gained prominence. The government’s repeated promises to create a “society where women shine” yielded only incremental change, but activism on issues such as harassment and unequal pay grew. LGBT communities also became more visible, with municipalities offering partnership certificates to same‑sex couples and pop culture celebrating queer identities.

By the late 2010s the Heisei generation had come of age. People who had grown up with anime, the internet and deflation now grappled with precarious employment, ageing parents and the looming cost of social security. Emperor Akihito, citing age and health, abdicated on April 30 2019—the first abdication in two centuries—and passed the Chrysanthemum Throne to his son Naruhito, ushering in the Reiwa era. The Heisei years ended not with a bang but with a whisper of hope. The era leaves a complex legacy: a world‑beating technology and cultural industry, a still‑formidable economy, but also unresolved challenges of demographic decline, political inertia and vulnerability to natural disasters.

By the late 2010s the Heisei generation had come of age. People who had grown up with anime, the internet and deflation now grappled with precarious employment, ageing parents and the looming cost of social security. Emperor Akihito, citing age and health, abdicated on April 30 2019—the first abdication in two centuries—and passed the Chrysanthemum Throne to his son Naruhito, ushering in the Reiwa era. The Heisei years ended not with a bang but with a whisper of hope. The era leaves a complex legacy: a world‑beating technology and cultural industry, a still‑formidable economy, but also unresolved challenges of demographic decline, political inertia and vulnerability to natural disasters.

Looking back, the Heisei era can be read as Japan’s coming‑of‑age story. The naïve optimism of the bubble years gave way to the sobering realisation that economies can stagnate and societies must adapt. The tragedies of 1995 and 2011 demonstrated both the fragility of modern infrastructure and the strength of human solidarity. Pop culture blossomed not despite economic hardship but perhaps because of it, offering escapism and community. Politically, the era illustrated that no party holds a monopoly on power forever and that democratic systems must evolve to remain legitimate. As we move into the Reiwa era, Japan’s challenges—ageing, climate change, technological transformation—resonate with global concerns. But the resilience, creativity and civic spirit cultivated during Heisei provide a toolkit for confronting the future. Stay tuned for the next instalment, where we explore how the Reiwa era has built upon—or departed from—its Heisei heritage.